Text analysis of the Mueller Report

By Rich

April 19, 2019

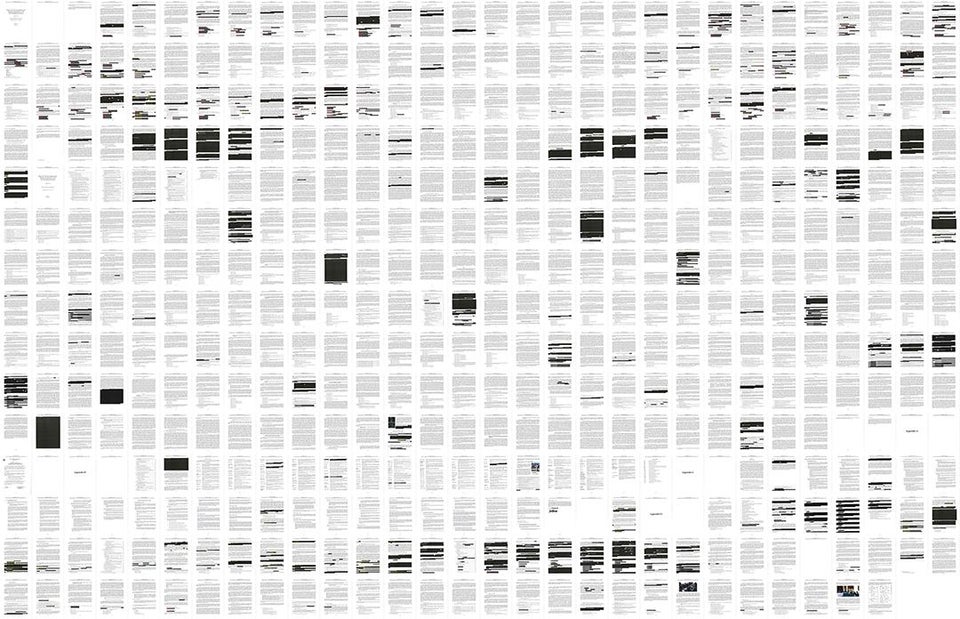

All 448 pages of the redacted report, with redacted setions shown in black. Source: LA Times

After years of investigation, the Department of Justice released a redacted copy of the Mueller Report on Thursday April 18, 2019. The report weighs in at a hefty 448 pages, and covers everything from Russian interference in 2016 presidential election, to the private testimony of Michael Cohen, and whether or not President Trump may have obstructed justice.

I don’t have all day to read this report, but I am interested to see what I can learn in a short afternoon by scraping the report and doing a cursory text and sentiment analysis.

I’m going to rely on two main packages: pdftools for scraping the text of the report, and tidytext for general text mining functions.

library(pdftools)

library(tidytext)

library(dplyr)

library(stringr)

library(tidyr)

library(ggplot2)

library(reshape2)

library(wordcloud)First, let’s grab the raw text from the file, and replace line break characters \r\n with spaces.

d <- pdf_text("~/Documents/Github/junkyard/mueller/report.pdf")

d <- str_replace_all(d, "\r\n", " ")Each page is an element in the vector d, so we can easily access any page by indexing it.

cat(d[1]) # page 1: the title## U.S. Department of Justice

## Attorney Work Product // May Contain Material Protected Under Fed. R. Crim. P. 6(e)

##

##

##

##

## Report On The Investigation Into

## Russian Interference In The

## 2016 Presidential Election

## Volume I of II

##

##

## Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, III

## Submitted Pursuant to 28 C.F.R. § 600.8(c)

##

##

##

##

## Washington, D.C.

##

## March 2019cat(d[300]) # page 300## U.S. Department of Justice

## Attorney Work Product // May Contain Material Protected Under Fed. R. Crim. P. 6(e)

##

##

##

## investigation and any grand jury proceedings that might flow from the inquiry. Even if the removal

## of the lead prosecutor would not prevent the investigation from continuing under a new appointee,

## a factfinder would need to consider whether the act had the potential to delay further action in the

## investigation, chill the actions of any replacement Special Counsel, or otherwise impede the

## investigation.

##

## A threshold question is whether the President in fact directed McGahn to have the Special

## Counsel removed. After news organizations reported that in June 2017 the President had ordered

## McGahn to have the Special Counsel removed, the President publicly disputed these accounts, and

## privately told McGahn that he had simply wanted McGahn to bring conflicts of interest to the

## Department of Justice’s attention. See Volume II, Section II.I, infra. Some of the President’s

## specific language that McGahn recalled from the calls is consistent with that explanation.

## Substantial evidence, however, supports the conclusion that the President went further and in fact

## directed McGahn to call Rosenstein to have the Special Counsel removed.

##

## First, McGahn’s clear recollection was that the President directed him to tell Rosenstein

## not only that conflicts existed but also that “Mueller has to go.” McGahn is a credible witness

## with no motive to lie or exaggerate given the position he held in the White House.601 McGahn

## spoke with the President twice and understood the directive the same way both times, making it

## unlikely that he misheard or misinterpreted the President’s request. In response to that request,

## McGahn decided to quit because he did not want to participate in events that he described as akin

## to the Saturday Night Massacre. He called his lawyer, drove to the White House, packed up his

## office, prepared to submit a resignation letter with his chief of staff, told Priebus that the President

## had asked him to “do crazy shit,” and informed Priebus and Bannon that he was leaving. Those

## acts would be a highly unusual reaction to a request to convey information to the Department of

## Justice.

##

## Second, in the days before the calls to McGahn, the President, through his counsel, had

## already brought the asserted conflicts to the attention of the Department of Justice. Accordingly,

## the President had no reason to have McGahn call Rosenstein that weekend to raise conflicts issues

## that already had been raised.

##

## Third, the President’s sense of urgency and repeated requests to McGahn to take immediate

## action on a weekend—“You gotta do this. You gotta call Rod.”—support McGahn’s recollection

## that the President wanted the Department of Justice to take action to remove the Special Counsel.

## Had the President instead sought only to have the Department of Justice re-examine asserted

## conflicts to evaluate whether they posed an ethical bar, it would have been unnecessary to set the

## process in motion on a Saturday and to make repeated calls to McGahn.

##

## Finally, the President had discussed “knocking out Mueller” and raised conflicts of interest

## in a May 23, 2017 call with McGahn, reflecting that the President connected the conflicts to a plan

## to remove the Special Counsel. And in the days leading up to June 17, 2017, the President made

## clear to Priebus and Bannon, who then told Ruddy, that the President was considering terminating

##

## 601

## When this Office first interviewed McGahn about this topic, he was reluctant to share detailed

## information about what had occurred and only did so after continued questioning. See McGahn 12/14/17

## 302 (agent notes).

##

## 88Let’s do some light cleaning and formatting: tokenize all words, index the postion of each word within its page and the document overall, remove stop words, and remove numeric tokens.

text_df <- tibble(page = 1:length(d), text = d)

df <- text_df %>%

unnest_tokens(word, text) %>%

group_by(page) %>%

mutate(page_ind = row_number(page),

page_length = length(page)) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(pos_page = page_ind/page_length,

doc_ind = 1:nrow(.),

pos_doc = doc_ind/nrow(.)) %>%

anti_join(stop_words) %>%

filter(!str_detect(word, "[:digit:]"))Now, I join sentiment scores (either positive or negative) for every word in the doc, using the sentiment lexicon from Bing Liu and collaborators, calculate the number of positive and negative words on each page, and normalize this score across the document. I had to remove the string “trump” because it’s used so much in the document, and actually classifies as a positive word, which is misleading. As expected given the nature of the investigation, the Mueller report is a pretty negative document.

p <- df %>%

inner_join(get_sentiments("bing")) %>%

filter(word != "trump") %>%

count(page, sentiment) %>%

spread(sentiment, n, fill = 0) %>%

mutate(sentiment = positive - negative,

sentiment = sentiment/max(abs(sentiment)),

dir = ifelse(sentiment >=0, "up","dn"))

p %>%

ggplot(aes(page, sentiment, fill = dir)) +

geom_col() +

labs(title = "The Mueller Report is generally negative",

subtitle = "Relative sentiment per page",

x = "Page number",

y = "Normalized sentiment") +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(1,-1)) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position='none')

We can see what’s going on in the most negative and positive pages like so.

Ironically, according to the words themselves, the most “positive” page of the report (247) concerns former FBI director James Comey’s private dinner with Trump, where Trump allegedly requested him to pledge loyalty to him. This old story was covered in everything from the Times to the Washington Post and Economist.

top <- p %>% top_n(1, wt = sentiment) %>% pull(page)

bot <- p %>% top_n(-1, wt = sentiment) %>% pull(page)

cat(d[top])## U.S. Department of Justice

## Attorney Work Product // May Contain Material Protected Under Fed. R. Crim. P. 6(e)

##

##

##

## and having Yanukovych, the Ukrainian President ousted in 2014, elected to head that republic.923

## That plan, Manafort later acknowledged, constituted a “backdoor” means for Russia to control

## eastern Ukraine.924 Manafort initially said that, if he had not cut off the discussion, Kilimnik would

## have asked Manafort in the August 2 meeting to convince Trump to come out in favor of the peace

## plan, and Yanukovych would have expected Manafort to use his connections in Europe and

## Ukraine to support the plan.925 Manafort also initially told the Office that he had said to Kilimnik

## that the plan was crazy, that the discussion ended, and that he did not recall Kilimnik asking

## Manafort to reconsider the plan after their August 2 meeting.926 Manafort said Grand Jury

##

## that he reacted negatively to Yanukovych sending—years later—an “urgent”

## request when Yanukovych needed him.927 When confronted with an email written by Kilimnik on

## or about December 8, 2016, however, Manafort acknowledged Kilimnik raised the peace plan

## again in that email.928 Manafort ultimately acknowledged Kilimnik also raised the peace plan in

## January and February 2017 meetings with Manafort,Grand Jury

## 929

##

##

##

## Second, Manafort briefed Kilimnik on the state of the Trump Campaign and Manafort’s

## plan to win the election.930 That briefing encompassed the Campaign’s messaging and its internal

## polling data. According to Gates, it also included discussion of “battleground” states, which

## Manafort identified as Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Minnesota.931 Manafort did not

## refer explicitly to “battleground” states in his telling of the August 2 discussion, Grand Jury

## 32

##

##

##

##

## prime minister. The plan emphasized that Yanukovych would be an ideal candidate to bring peace to the

## region as prime minister of the republic, and facilitate the reintegration of the region into Ukraine with the

## support of the U.S. and Russian presidents. As noted above, according to GJ the written

## documentation describing the plan, for the plan to work, both U.S. and Russian support were necessary.

## Grand Jury 2/21/18 Email, Manafort, Ward, & Fabrizio, at 3-5.

## 923

## Manafort 9/11/18 302, at 4; Grand Jury

##

## 924

## Grand Jury

## 925

## Manafort 9/11/18 302, at 4.

## 926

## Manafort 9/12/18 302, at 4.

## 927

## Grand Jury Manafort 9/11/18 302, at 5; Manafort 9/12/18

## 302, at 4.

## 928

## Manafort 9/12/18 302, at 4; Investigative Technique

## 929Grand Jury Documentary

## evidence confirms the peace-plan discussions in 2018. 2/19/18 Email, Fabrizio to Ward (forwarding email

## from Manafort); 2/21/18 Email, Manafort to Ward & Fabrizio.

## 930

## Manafort 9/11/18 302, at 5.

## 931

## Gates 1/30/18 302, at 3, 5.

## 932

## Grand Jury

##

## 140The most “negative page” of the document (378) addresses legal definitions of collusion, obstruction, and so on. With sentences the following, it’s easy to see why this page scores high on negative sentiment.

“[a]s used in [S]ection 1505, the term ‘corruptly’ means acting with an improper purpose, personally or by influencing another, including by making a false or misleading statement, or withholding, concealing, altering, or destroying a document or other information.

cat(d[bot])## U.S. Department of Justice

## Attorney Work Product // May Contain Material Protected Under Fed. R. Crim. P. 6(e)

##

##

##

## Aguilar, 515 U.S. at 599-602. In several obstruction cases, the Court has imposed a nexus test that

## requires that the wrongful conduct targeted by the provision be sufficiently connected to an official

## proceeding to ensure the requisite culpability. Marinello, 138 S. Ct. at 1109; Arthur Andersen,

## 544 U.S. at 707-708; Aguilar, 515 U.S. at 600-602. Section 1512(c)(2) has been interpreted to

## require a similar nexus. See, e.g., United States v. Young, 916 F.3d 368, 386 (4th Cir. 2019);

## United States v. Petruk, 781 F.3d 438, 445 (8th Cir. 2015); United States v. Phillips, 583 F.3d

## 1261, 1264 (10th Cir. 2009); United States v. Reich, 479 F.3d 179, 186 (2d Cir. 2007). To satisfy

## the nexus requirement, the government must show as an objective matter that a defendant acted

## “in a manner that is likely to obstruct justice,” such that the statute “excludes defendants who have

## an evil purpose but use means that would only unnaturally and improbably be successful.”

## Aguilar, 515 U.S. at 601-602 (internal quotation marks omitted); see id. at 599 (“the endeavor

## must have the natural and probable effect of interfering with the due administration of justice”)

## (internal quotation marks omitted). The government must also show as a subjective matter that

## the actor “contemplated a particular, foreseeable proceeding.” Petruk, 781 F.3d at 445. Those

## requirements alleviate fair-warning concerns by ensuring that obstructive conduct has a close

## enough connection to existing or future proceedings to implicate the dangers targeted by the

## obstruction laws and that the individual actually has the obstructive result in mind.

##

## b. Courts also seek to construe statutes to avoid due process vagueness concerns. See, e.g.,

## McDonnell v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 2355, 2373 (2016); Skilling v. United States, 561 U.S. 358,

## 368, 402-404 (2010). Vagueness doctrine requires that a statute define a crime “with sufficient

## definiteness that ordinary people can understand what conduct is prohibited” and “in a manner that

## does not encourage arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement.” Id. at 402-403 (internal quotation

## marks omitted). The obstruction statutes’ requirement of acting “corruptly” satisfies that test.

##

## “Acting ‘corruptly’ within the meaning of § 1512(c)(2) means acting with an improper

## purpose and to engage in conduct knowingly and dishonestly with the specific intent to subvert,

## impede or obstruct” the relevant proceeding. United States v. Gordon, 710 F.3d 1124, 1151 (10th

## Cir. 2013) (some quotation marks omitted). The majority opinion in Aguilar did not address the

## defendant’s vagueness challenge to the word “corruptly,” 515 U.S. at 600 n. 1, but Justice Scalia’s

## separate opinion did reach that issue and would have rejected the challenge, id. at 616-617 (Scalia,

## J., joined by Kennedy and Thomas, JJ., concurring in part and dissenting in part). “Statutory

## language need not be colloquial,” Justice Scalia explained, and “the term ‘corruptly’ in criminal

## laws has a longstanding and well-accepted meaning. It denotes an act done with an intent to give

## some advantage inconsistent with official duty and the rights of others.” Id. at 616 (internal

## quotation marks omitted; citing lower court authority and legal dictionaries). Justice Scalia added

## that “in the context of obstructing jury proceedings, any claim of ignorance of wrongdoing is

## incredible.” Id. at 617. Lower courts have also rejected vagueness challenges to the word

## “corruptly.” See, e.g., United States v. Edwards, 869 F.3d 490, 501-502 (7th Cir. 2017); United

## States v. Brenson, 104 F.3d 1267, 1280-1281 (11th Cir. 1997); United States v. Howard, 569 F.2d

## 1331, 1336 n.9 (5th Cir. 1978). This well-established intent standard precludes the need to limit

## the obstruction statutes to only certain kinds of inherently wrongful conduct.1083

##

##

## 1083

## In United States v. Poindexter, 951 F.2d 369 (D.C. Cir. 1991), the court of appeals found the

## term “corruptly” in 18 U.S.C. § 1505 vague as applied to a person who provided false information to

## Congress. After suggesting that the word “corruptly” was vague on its face, 951 F.2d at 378, the court

##

## 166

## U.S. Department of Justice

## Attorney Work Product // May Contain Material Protected Under Fed. R. Crim. P. 6(e)

##

##

##

## c. Finally, the rule of lenity does not justify treating Section 1512(c)(2) as a prohibition on

## evidence impairment, as opposed to an omnibus clause. The rule of lenity is an interpretive

## principle that resolves ambiguity in criminal laws in favor of the less-severe construction.

## Cleveland v. United States, 531 U.S. 12, 25 (2000). “[A]s [the Court has] repeatedly emphasized,”

## however, the rule of lenity applies only if, “after considering text, structure, history and purpose,

## there remains a grievous ambiguity or uncertainty in the statute such that the Court must simply

## guess as to what Congress intended.” Abramski v. United States, 573 U.S. 169, 188 n.10 (2014)

## (internal quotation marks omitted). The rule has been cited, for example, in adopting a narrow

## meaning of “tangible object” in an obstruction statute when the prohibition’s title, history, and list

## of prohibited acts indicated a focus on destruction of records. See Yates v. United States, 135 S.

## Ct. 1074, 1088 (2015) (plurality opinion) (interpreting “tangible object” in the phrase “record,

## document, or tangible object” in 18 U.S.C. § 1519 to mean an item capable of recording or

## preserving information). Here, as discussed above, the text, structure, and history of Section

## 1512(c)(2) leaves no “grievous ambiguity” about the statute’s meaning. Section 1512(c)(2)

## defines a structurally independent general prohibition on obstruction of official proceedings.

##

## 5. Other Obstruction Statutes Might Apply to the Conduct in this Investigation

##

## Regardless whether Section 1512(c)(2) covers all corrupt acts that obstruct, influence, or

## impede pending or contemplated proceedings, other statutes would apply to such conduct in

## pending proceedings, provided that the remaining statutory elements are satisfied. As discussed

## above, the omnibus clause in 18 U.S.C. § 1503(a) applies generally to obstruction of pending

## judicial and grand proceedings.1084 See Aguilar, 515 U.S. at 598 (noting that the clause is “far

## more general in scope” than preceding provisions). Section 1503(a)’s protections extend to

## witness tampering and to other obstructive conduct that has a nexus to pending proceedings. See

## Sampson, 898 F.3d at 298-303 & n.6 (collecting cases from eight circuits holding that Section

## 1503 covers witness-related obstructive conduct, and cabining prior circuit authority). And

## Section 1505 broadly criminalizes obstructive conduct aimed at pending agency and congressional

## proceedings.1085 See, e.g., United States v. Rainey, 757 F.3d 234, 241-247 (5th Cir. 2014).

##

##

##

## concluded that the statute did not clearly apply to corrupt conduct by the person himself and the “core”

## conduct to which Section 1505 could constitutionally be applied was one person influencing another person

## to violate a legal duty. Id. at 379-386. Congress later enacted a provision overturning that result by

## providing that “[a]s used in [S]ection 1505, the term ‘corruptly’ means acting with an improper purpose,

## personally or by influencing another, including by making a false or misleading statement, or withholding,

## concealing, altering, or destroying a document or other information.” 18 U.S.C. § 1515(b). Other courts

## have declined to follow Poindexter either by limiting it to Section 1505 and the specific conduct at issue in

## that case, see Brenson, 104 F.3d at 1280-1281; reading it as narrowly limited to certain types of conduct,

## see United States v. Morrison, 98 F.3d 619, 629-630 (D.C. Cir. 1996); or by noting that it predated Arthur

## Andersen’s interpretation of the term “corruptly,” see Edwards, 869 F.3d at 501-502.

## 1084

## Section 1503(a) provides for criminal punishment of:

## Whoever . . . corruptly or by threats or force, or by any threatening letter or

## communication, influences, obstructs, or impedes, or endeavors to influence, obstruct, or

## impede, the due administration of justice.

## 1085

## Section 1505 provides for criminal punishment of:

##

## 167We can take a closer look at the words that contribute towards positive and negative scores.

bing_word_counts <- df %>%

inner_join(get_sentiments("bing")) %>%

filter(word != "trump") %>%

count(word, sentiment, sort = TRUE) %>%

ungroup()

bing_word_counts %>%

group_by(sentiment) %>%

top_n(10) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(word = reorder(word, n)) %>%

ggplot(aes(word, n, fill = sentiment)) +

geom_col(show.legend = FALSE) +

facet_wrap(~sentiment, scales = "free_y") +

labs(y = "Contribution to sentiment",

x = NULL) +

coord_flip() +

theme_minimal()

And view the top 100 words in the document, colored by sentiment.

df %>%

inner_join(get_sentiments("bing")) %>%

filter(word != "trump") %>%

count(word, sentiment, sort = TRUE) %>%

acast(word ~ sentiment, value.var = "n", fill = 0) %>%

comparison.cloud(colors = c("red", "lightblue"),

max.words = 100)

That’s all that quick and dirty analysis will allow. Enjoy reading the full version of the report in your copious free time!

- Posted on:

- April 19, 2019

- Length:

- 16 minute read, 3311 words

- See Also: